Seventy years ago this month, the Hudson Valley cities of Kingston and Newburgh, NY proudly stood at the center of a transformative public health experiment. The Newburgh-Kingston Caries-Flourine Study, conducted between 1945 and 1955, was one the most influential demonstrations in the history of public medicine. It proved, with a very high level of rigor, that children can ingest a safe amount of fluoride added to community water supplies and have up to 60% fewer cavities than children who drink unfluoridated water.

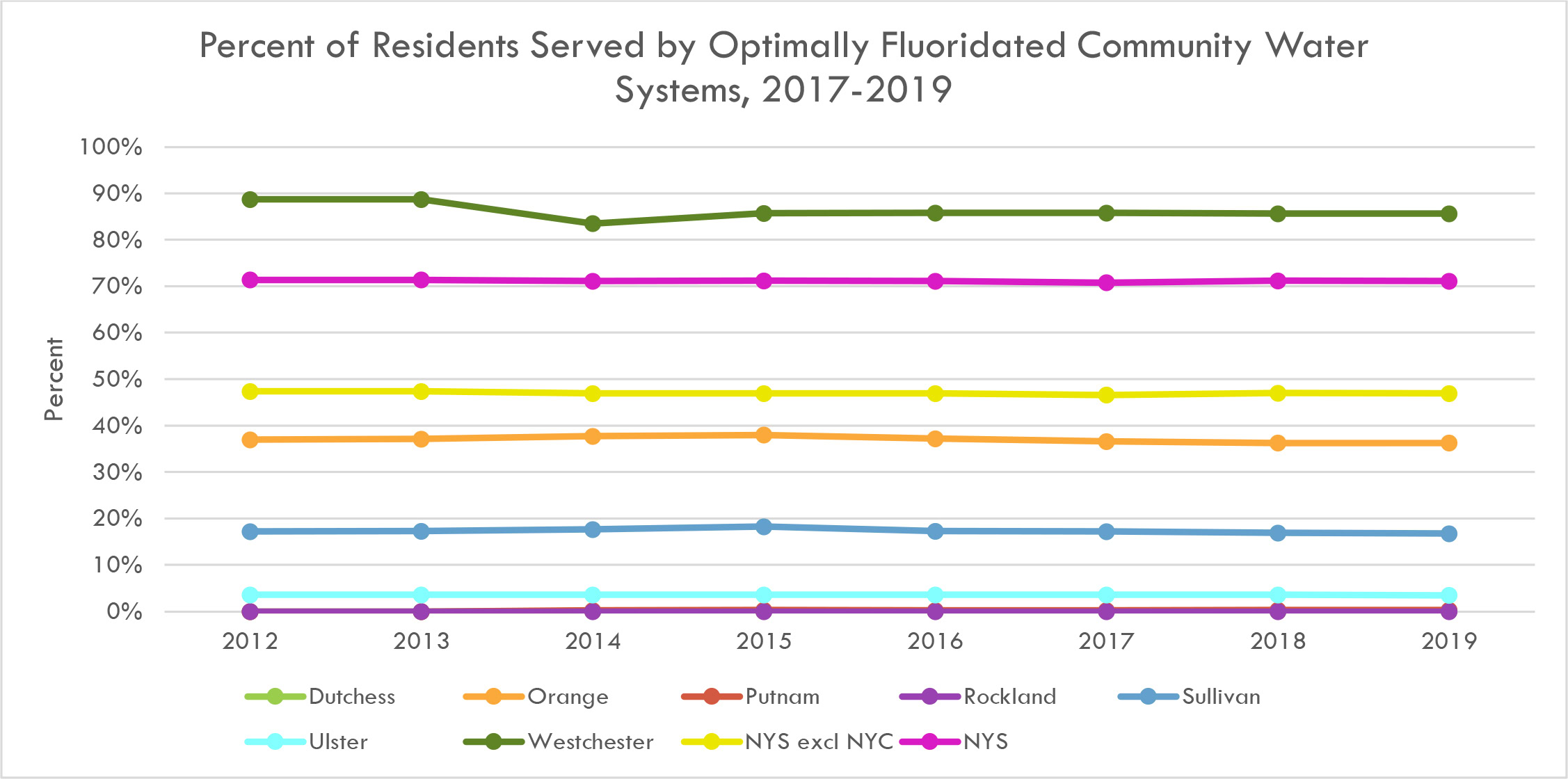

The study was a scientific basis for community water fluoridation across the nation. Today, over 72% of Americans on public water systems primarily drink community fluoridated water. But even though Kingston helped proved that fluoride works, it has refused to use it.

Kingston does not use fluoride, and only 3% of Ulster County’s population has fluoridated water. By comparison, 88% of Westchester County residents drink fluoridated water. Their children have just one-third the cavities of children in Ulster County, despite similar levels of healthcare access and insurance coverage.

There is now a campaign to change this. Find out more at Flouridate Kingston.

Why? How has a city that helped prove the power of fluoridation rejected it for three-quarters of a century? And what has that decision cost generations of families, in dollars, decay, and pain?

The answer is a mix of local politics, cultural upheaval, and Cold War hysteria. It’s a cautionary tale of how public health policy can get hijacked by misinformation, and how paranoia can cut across both the political left and right.

The Origins of Fluoridation

In the 1910s, dental researchers and chemists began investigations into curious cases of “mottled teeth,” where the appearance of the tooth conflicted with a lack of actual tooth decay. A chemist named H.V. Churchill, working for Alcoa, discovered that the naturally-occurring mineral fluoride in the cause.

As the Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s National Institute of Health was constituted in the 1930s, a 38 year-old dental officer named H. Trendley Dean was named chief scientist of dental research. His first assignment was threefold: to determine whether too much fluoride caused mottled teeth, if there was an ideal concentration of fluoride that would still provide a benefit, and if naturally-occurring fluoride could be removed from water.

This seemingly obscure research had a public relations breakthrough in 1942, when a Reader’s Digest story titled The Town Without a Toothache featured a Texas town with naturally occurring fluoride called “miracle water,” resulting in a startling lack of dental disease and cavities.

Dean launched official U.S. fluoridation trials in Michigan and Illinois in 1945.

The Newburgh-Kingston Study

Around the same time, the New York State Department of Health’s David Ast kicked off another fluoride study, to test a plan for reducing tooth decay. Newburgh and Kingston agreed to participate, as cities with relatively similar populations and demographics in the Hudson Valley.

Newburgh’s water would be fluoridated to 1.0 parts per million (ppm), while Kingston would remain unfluoridated as a control city.

A 10 to 12 year experiment… was begun in June, 1944 at two neighboring cities in New York: Newburgh and Kingston. These towns have similar water supplies, population groups, climatic conditions, economic conditions and sources of food supply.

To the Newburgh water supply has been added fluorine in the correct amount. Kingston will continue using fluorine-free water. In the meantime, extensive physical and dental examination are being made of pre-school age children in both towns. A group of adults past 50 will be examined during the experiment to determine the effects of fluorine in small concentrations on persons past middle age.

New York Daily News, July 22, 1945

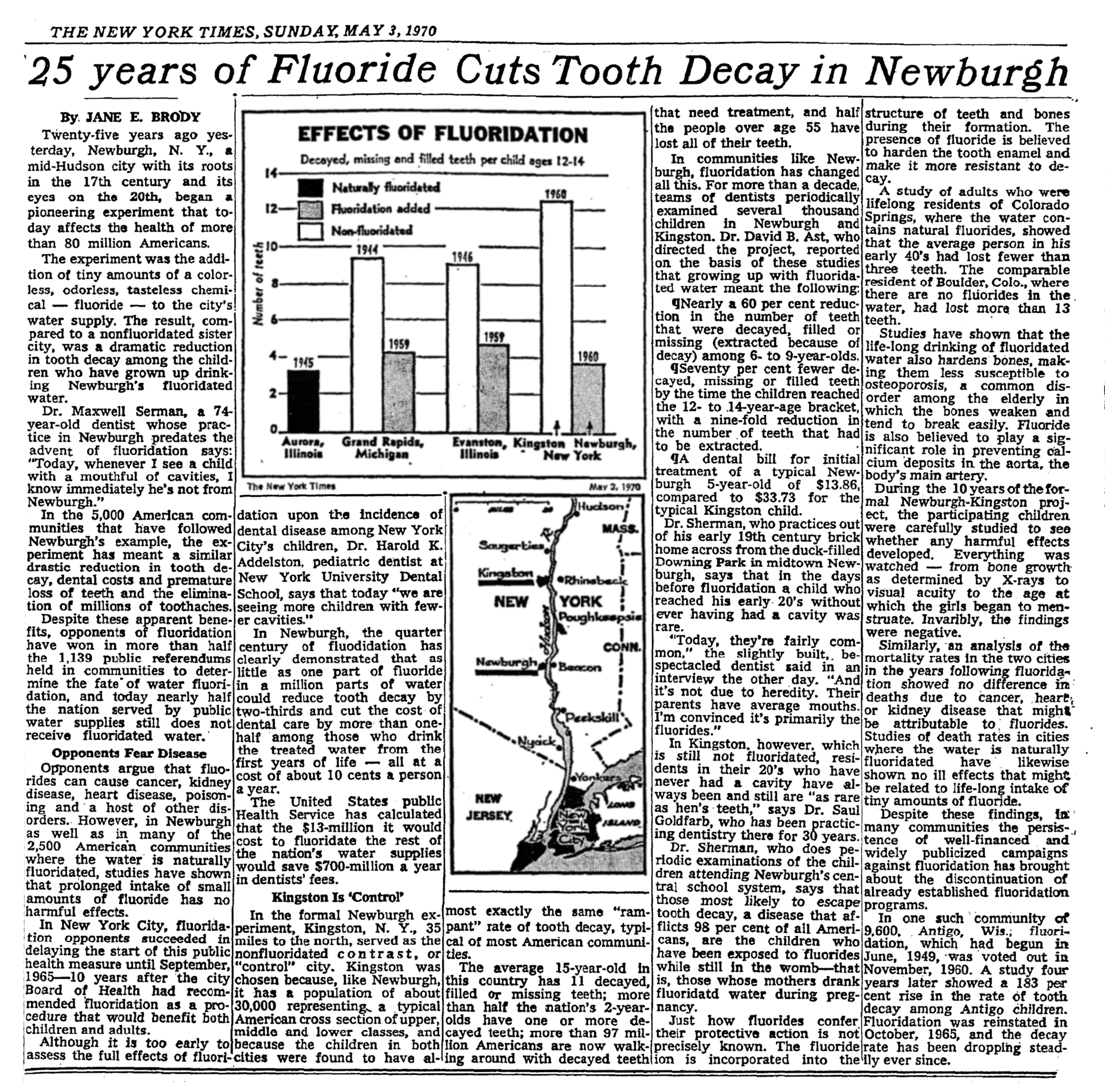

By 1949, the trial was showing drastic early results with a 32% reduction in cavities in Newburgh schoolchildren. Cities around the country were clamoring to be allowed to fluoridate their water before the trials were complete. In June of 1950, the Public Health Service announced its support for community fluoridation, followed by the New York State Department of Health.

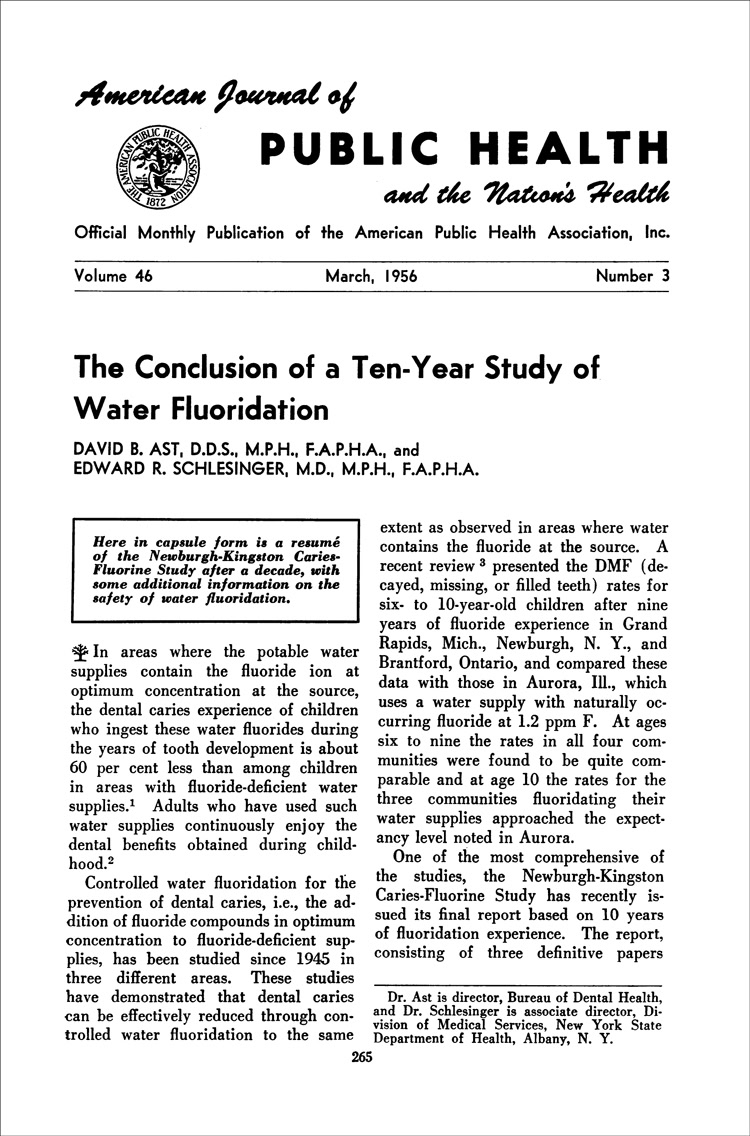

In 1955, the Newburgh-Kingston study was feted as complete; children’s tooth decay in Newburgh declined by 60% compared to Kingston’s unfluoridated water. Saugerties, Catskill and Port Ewen all took steps towards fluoridation.

Dr. Edward Schlesinger of the New York State Health Department said that “all reports to date confirm earlier findings that water fluoridation has no demonstrable effect on children except for the known dental benefits of reduction in tooth decay.”

To Fluoridate or Not to Fluoridate

Based on those results, one would expect that Mid-Hudson Valley cities would rush to join Newburgh in fluoridating their water. And it certainly seemed like that at first.

But Ulster County’s Commissioner of Health, Dr. Dudley Hargrave, cautioned that “fluoridation has been discussed pro and con in Kingston… it hasn’t become an issue yet, but may in the future.”

In March of 1956, a contentious water fluoridation panel was held at a Jewish community center on Wall Street in Kingston. It included 35 physicians and dentists from the area, as well as then-Mayor Frederick H. Stang. Dr. David Smith of the New York State Department of Health spoke in favor of fluoridation, while a pair of rogue dentists from Beacon and Kingston spoke against it.

Public health authorities and local dental associations like the Ulster-Greene Dental Study Club were quickly flabbergasted by what they called “charlatans, pamphleteers and anti-causists” who caused “all scientific evidence [to be] distorted to instill doubt and even fear into the minds of the medically uneducated.”

“A tremendous number of medical, dental and scientific organizations have reviewed the effects of flouridation and have concluded that artificial fluoridation of public water supplies in the amount that we shall use in Poughkeepsie is to be recommended as one effective means for the partial control of dental decay in youngsters… The conservative groups, which are not actually against fluoridation, but merely want more and more evidence of its good effects, have been supported by other factions which appear to consider dental decay as an essential part of the ‘American way of life’ and any attempt to prevent and control decay as being against community interests. There will always be elements (in society) which are against progress and which refuse to accept valid proof of the beneficial effects of community programs.”

Poughkeepsie Health Officer Dr. Kraus, 1952

Internationally, those “cautious concerns” were being stoked into a full-on fluoride panic.

Alternative health enthusiasts, followers of Rudolph Steiner and anthroposophy, religious traditionalists, and anti-communist crusaders all found common cause in resisting what they saw as an undemocratic intrusion into their bodies. Society’s ills could be blamed on invisible toxins or contaminants that invade the body through food and water. What began as a cautious public health experiment had, by the mid-1950s, become a cultural battleground that transcended the left vs. right paradigm, as lampooned in the 1964 Stanley Kubrick film Doctor Strangelove:

While Newburgh, Middletown, Poughkeepsie, Catskill and Hudson all signed on to community water fluoridation, an ongoing debate over whether to fluoridate Kingston’s water went on for at least 25 years:

1962

Several Parent Teacher Associations, in concert with a Citizens Committee for Fluoridation, endorsed water fluoridation in Kingston. Dr. Stephen McGrath, a local physician, offered a utilitarian argument in support:

“Dental welfare costs were $17,000 for the county in 1960… the amount spent in Kingston… alone amounts to more than it would cost to fluoridate the water supply. Fluoridation would be an economy measure for every family by reducing their dental bills by two thirds.”

A “Kingston Pure Water Committee” was formed in response, claiming that the PTA votes were heavily manipulated, that the only safe way to administer fluorides was “on an individual basis,” and filing a 300-signature petition that stated that fluoridation is “an origination of communistic action to bore from within and conquer by getting all of us to be cowlike in time…”

In response, the Citizens Committee for Fluoridation said the petition was an “insult to the integrity of the citizens of Kingston… what disturbs us more is the possibility of a loud minority like this causing delay of fluoridation in Kingston. Let’s face it, fluoridation as a public health measure, has been proven in some of the largest cities in America, and is as inevitable as pasteurization and immunization was.”

On March 6, the Kingston Common Council declared that fluoridation in Kingston would require a citywide referendum to be enacted, and a week later, the city’s Water Board ruled against the fluoridation of the city’s water supply, despite the endorsements of the Ulster County Health, Medical and Dental Societies.

1967-1968

A November front page headline in the Daily Freeman read “Urge Immediate Fluoridation of County Water,” quoting the Ulster County Dental Society, Medical Society and the Board of Health asserting that “Kingston children require more than twice as many dental services as the Newburgh group.” The groups stated that the average cost of a year’s worth dental treatment for children in Kingston was close to double or triple what it costs for children in Newburgh.

The Daily Freeman then asked in a cover story, “Fluoridation: What Happened?”

“For more than two years, the question has not been asked in the Kingston area and, in fact, remains unanswered after more than 15 years of debate… A definite lack of voices has added to the general apathy and nonconcern for the fluoridation issue that at times rocked the Common Council chambers as well as town board rooms in the past.

Daily Freeman, December 18, 1968

1970-1971

Another push happened in 1970, with the Ulster County Medical Society and Ulster County Dental Society endorsing fluoridation in Kingston. In response, Kingston 13th Ward Alderman Titus B. Sims requested Newburgh mayor George McKneally’s feedback on how fluoridation worked out for his city.

McKneally wrote back, saying “fluoridation was one of the best public health programs his city had ever had, and that it had reduced tooth decay in Newburgh’s children by almost 60 per cent.”

Local journalist Hugh Reynolds wrote in his column:

“Make no mistake, the alderman are scared on this fluoridation issue. This is THE big one. This is the one that could put them all out of office. Self-preservation is the overriding instinct of most politicians.”

The Kingston Area Chamber of Commerce was a venue for the debate. In September, Dr. Naham Cohns of the New York State Health Department spoke in favor of fluoridating the city’s water at a September meeting. In November, in the name of balance, The Chamber hosted a rebuttal by Kingston resident and organic food author C.E. Burtis.

“The earth is smothering in a sea of poison and the addition of fluoride, an insane and ludicrous proposal would only hasten the process… fluoride is a lot of damned nonsense. Not only nonsense but criminal activity.”

-C.E. Burtis, November 1970

The Kingston Common Council took up the issue yet again in early 1971. A Daily Freeman editorial wrote, “there is an emotional side to the controversy… some opponents denounce it as “mass suicide” or a communist plot to ruin the health of the people,” they said. “Painstaking studies have been done… further delay is a disservice to the children of the community.”

Rabbi Jonathan Eichhorn offered a “prayer for fluoridation” on New Year’s Day, exhorting the Common Council, “in a world of moral cowards, be thou a Man!” Eichhorn was roundly condemned by the Council for his intervention.

In response, Kingston’s Laws and Rules Committee issued a negative recommendation to the full Common Council. Alderman-at-Large T. Robert Gallo said “the Committee report is carried… Fluoridation is defeated.”

1975

The last push for fluoridation in Kingston to date was in 1975, when New York Governor Hugh L. Carey advocated for a fluoride mandate in holdout communities on Long Island, as well as Beacon, Hudson, Kingston, Middletown, Ossining, Peekskill and Tarrytown.

“These are the beginning steps in campaign to improve the quality of health and health care in New York State,” Carey said.

The Ulster County Conservative Party said, “at this time when pollution is uppermost in the minds of our citizens, some of us want to deliberately add poison to our water.”

They were joined by Democratic Assemblyman Maurice Hinchey, who said that he would vote against the Governor’s fluoridation proposal.

“The issue isn’t health in this case… it’s freedom of choice,” he said. “I will not vote for any bill that mandates the use of fluorides in drinking water.”

The Common Council voted 9-4 in a memorializing resolution against the proposal. Carey’s office said that Kingston’s Council suffered a “total lack of scientific evidence to indicate that any harmful side effects result from drinking fluoridated water.”

However, the New York State Assembly voted against the Carey fluoride proposal. Carey’s attention and political capital was then consumed in trying to save New York City from a fiscal crisis, so the proposal went away.

Are the Fluoride Wars Coming Back?

In 2008, anti-fluoride forces scored a major victory when the Poughkeepsie Joint Water Board, which serves 80,000 people across the city and town of Poughkeepsie, as well as Hyde Park and Wappingers Falls, voted to stop their decades long-practice of adding fluoride to the community water supply. Part of the issue was the unresponsiveness of state Health Department officials, which did not respond to a list of specific questions from the board about the safety of fluoride.

In 2013, dentists in Poughkeepsie and Kingston revived the call for fluoridation, to no avail.

But the national resurgence of the fluoride debate has led to a new development in the City of Albany, the largest unfluoridated city in New York State.

Last year, the city bucked decades of trends with a 12-0 Common Council vote to join its neighbors in Guilderland, Schenectady and Troy in fluoridating its water. It’s expected that the city’s population of 100,000 will have about 0.7 parts per million of fluoride added to their water by year’s end.

The True Cost of Kingston’s Fluoride Stance

What has Kingston’s refusal to fluoridate cost our children? Over the past 80 years, it’s likely led to an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 more cavities than their peers in Newburgh. These are painful, preventable conditions that have cost local families millions in dental treatment and distress.

But the cost isn’t just financial. It’s symbolic.

For seven decades, Kingston has sat on the sidelines of a public health breakthrough it helped prove. The city celebrates science in theory while ignoring its benefits in practice. While Newburgh halved its cavity rates and Albany finally joined the modern era, Kingston remains stuck in a cycle of hesitation shaped by old fears, fringe ideologies, and a mistaken belief that public health efforts must infringe on personal liberty.

In 2025, the question is no longer whether fluoride is safe. It’s whether Kingston has the moral courage to reclaim its legacy. Will we protect the next generation from the mistakes of the past?