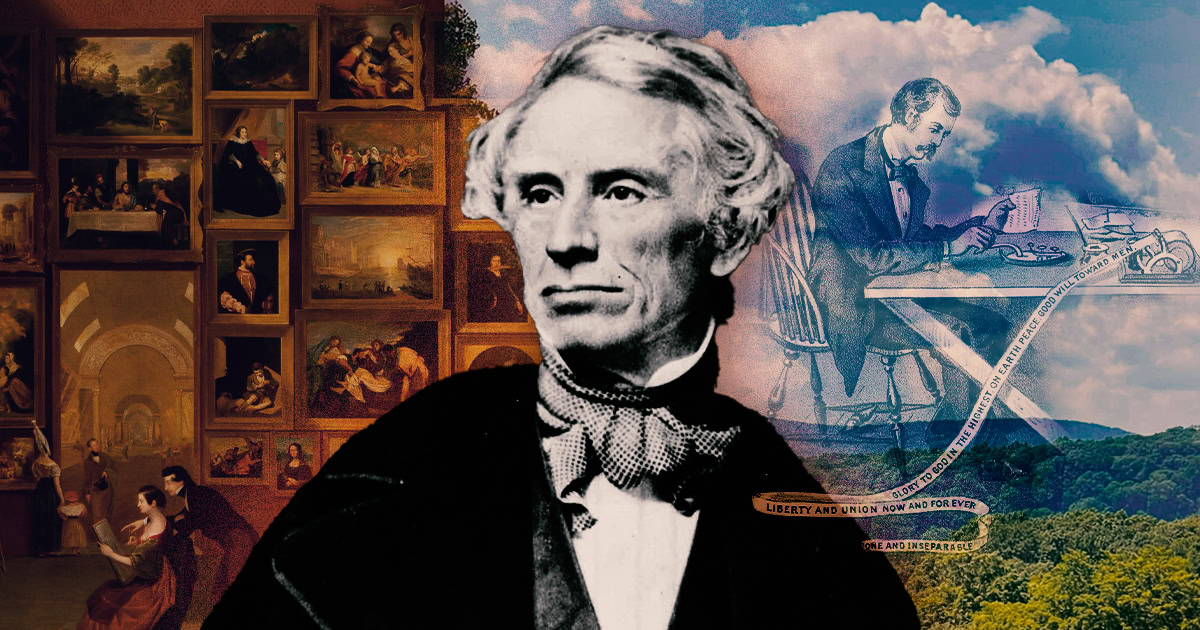

From the road, Locust Grove Estate is unassuming; Hudson Valley residents can easily drive past the sign a thousand times. But tucked away a few hundred feet from Route 9 is a painterly, 200-acre landscape and historic Italianate mansion, which stands as a physical reminder of an American who, in the 1800s, was considered on par with Leonardo da Vinci.

His name was Samuel F.B. Morse, and his genius was not just as an artist and inventor of the telegraph, but as part of a patriotic, international network of figures like Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette, the German scientist Alexander von Humboldt, and the Hudson Valley’s own James Fennimore Cooper.

His story took many twists and turns, not all of them noble, especially after the deaths of guiding lights like Lafayette and Cooper. But for all his faults, Morse left behind institutions that strengthened the American Republic: he established an international telegraph network, founded the National Academy of Design, helped establish Vassar College, and his invention helped the North win the Civil War decisively.

Telling his story also will require a couple of detours into the lives of lesser-known men who lived during the same time in the Hudson Valley: Poughkeepsie’s abolitionist preacher H.G. Ludlow, and Kingston’s Civil War spymaster George H. Sharpe.

This article is part of Kingston Creative’s “Hudson Valley Geniuses” series, weaving together local history, art, and still-standing landmarks into a living tapestry, told in the spirit of a universal history, where individual lives and places are seen as threads in the grand fabric of America’s progress. To get the next article in your inbox, sign up here.

Classical and Republican Beginnings

Samuel F.B. Morse was born in 1791 in Charlestown, Massachusetts, to Reverend Jedidiah Morse, who was a prominent clergyman and geographer. After graduating from Yale in 1810, where he studied both theology and the natural sciences, Morse pursued his first true passion: painting. He trained under the celebrated American artist Washington Allston and traveled to England in 1811 to study at the Royal Academy, absorbing the techniques of the old masters. Morse honed his skills, producing works like The Dying Hercules that revealed his ambition to place American art on equal footing with Europe’s finest.

Returning home in 1815, he jumped around as a portrait artist, painting figures like President John Adams, New York Governor and Erie Canal builder DeWitt Clinton, and the poet William Cullen Bryant. In his time in New York City, he became part of the city’s burgeoning intellectual and patriotic circles, and gained admission to James Fennimore Cooper’s Bread and Cheese Club, a republican group of writers, artists and statesmen, including Bryant, Washington Irving, Asher Durand, Thomas Cole, and future New York City mayor and Delaware & Hudson Canal president Philip Hone.

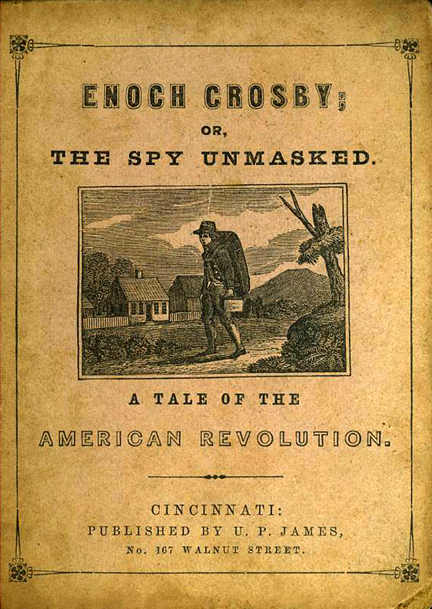

Morse began a lifelong friendship with Cooper, who at the time was known mostly for the success of his 1821 novel The Spy: A Tale of the Neutral Ground. The book drew on conversations with Cooper’s friend, Founding Father John Jay, about Jay’s experiences running an intelligence network in Westchester County during the Revolutionary War. The story’s protagonist, Harvey Birch, was loosely based on the real-life Westchester peddler Enoch Crosby, who was accused of being a double agent in the course of his intelligence activities in support of the Continental Army and Washington. Cooper turned the shadowy work of patriot spies into a distinctly American form of heroism, an ideal that blended courage, secrecy, and service to the republic.

Although Cooper is mostly remembered today for The Last of the Mohicans and the legend of Natty Bumpo, he was a political thinker steeped in Revolutionary intelligence history, and his works represented an American cultural offensive against deeply-entrenched oligarchism in Europe.

I have visited, in Europe, many countries, and what I have asserted of the fame of Mr. Cooper I assert from personal knowledge. In every city of Europe that I have visited, the works of Cooper were conspicuously placed in the windows of every book-shop. They are published as soon as he produces them in thirty-four different places in Europe. They have been seen by American travelers in the languages of Turkey and Persia, in Constantinople, in Egypt, at Jerusalem, at Isphahan.

Samuel Morse, 1839

Through his association with Cooper and the Bread and Cheese Club, Morse began interrogating his industry, the arts, for its potential to help refine American taste and mold a citizenry fit of contributing to a “more perfect Union,” as the Constitution preamble says. His 1822 commission, The House of Representatives, “depicts a cavernous chamber and its twenty-two monumental columns, dwarfing the legislators who prepare to work into the night, dramatizing the young republic’s seriousness, stability, and unostentatious grandeur.”

Frustrated with elite networks that controlled the fine arts in America, Morse then created the National Academy of Design, which would was not driven by rich collectors and patrons, but by the artists themselves. He said “every profession in society knows best what measures are necessary for its own improvement,” and set about creating a curriculum to elevate New York City artists and their supporters’ tastes. It was through the National Academy of Design that the Hudson River School, the first American school of art, exploded beyond Thomas Cole and Asher Durand into an international phenomenon that, at its best, mythologized the United States as the Eden for a new kind of republic of limitless possibilities.

Morse’s prominence then led him to meet the other great influence of his life, the French Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette, who in 1824 was engaged in a triumphant nationwide tour of the United States, including the Hudson River and the opening of the Erie Canal, that was tied to the memory of the Revolutionary War. Morse was commissioned by Mayor Philip Hone and the New York City government to paint the definitive portrait of Lafayette.

This is the man now before me, the very man who spent his youth, his fortune, and his time, to bring about (under Providence) our happy Revolution; the friend and companion of Washington, the terror of tyrants, the firm and consistent supporter of liberty … this is the man, the very identical man!

Samuel Morse, 1825

Morse’s eight-by-five foot portrait of the 68 year old Lafayette was displayed at the second National Academy of Design show. The painting features a radiant sunset sky, representing the triumphant close of Lafayette’s life, and an empty pedestal beside the busts of Washington and Franklin, awaiting the Marquis to join the trinity of heroes. It shows not only Lafayette the man, but the idea of him, an American icon who happened to be French.

Morse, Lafayette and Cooper in Paris

James Fennimore Cooper and his family moved to Paris in 1825, and Samuel Morse joined him in 1829, in what were to become the most pivotal years of his life. After losing his wife and parents in a short period of time, Morse worked feverishly on his epic painting Gallery of the Louvre, spending hours every day on raised platforms at the museum. The concept was bold: he wanted to create an art museum in one painting, with the goal of transmitting centuries of the Louvre’s treasures to Americans in a single, immortal canvas to help them cultivate a renaissance of republican virtues and taste, city by city.

The six by nine foot painting contains faithful copies of thirty-seven masterworks by Titian, Raphael, Leonardo, Veronese, Velázquez, and others. Like Raphael’s School of Athens, the composition was both a tribute and an invention; a fictional room filled with works never hung together, populated with real figures drawn from Morse’s circle, living and dead, in a kind of republican pantheon. Cooper himself appears with his wife and daughter, as does Morse, teaching art to his own daughter, and even his late wife Lucretia, inserted as an homage years after her death.

At the same time, Cooper was developing some of his most important work: a trio of books called The Bravo, The Heidenmauer and The Headsman, which all dealt with complex subjects of political underworlds, counter-revolutions, factional intrigues and European espionage that all worked to undermine the sovereignty of republics. Cooper’s goal was to show his fellow Americans the realities of one so-called republic in Venice, warning them that even republics can fall under oligarchic control, and that their freedoms can be taken away.

Cooper folded Morse into his daily routine: mornings of writing, afternoons in the Louvre bantering with Morse at his easel, evenings given to conversation with a rotating cast of Americans abroad. Cooper hovered over Morse’s shoulder while he worked, famously saying things like “Lay it on here, Samuel! More yellow; the nose is too short.” The legendary German scientist Alexander von Humboldt also spent days with Morse strolling through the Louvre; Humboldt would later champion Europe’s adoption of Morse’s telegraph as a tool for transmitting universal knowledge without restrictions.

Morse and Cooper became deeply involved in their friend Lafayette’s continued organizing in Paris; they met weekly at Cooper’s home regarding the issue of Polish independence from Russia. Lafayette would regale them with Revolutionary War stories, while Cooper and Morse raised money and awareness through their growing transatlantic political and cultural network.

The Telegraph

Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre turned out to be a financial flop, and he quit painting soon afterward. He wrote to Cooper, “Painting has been a smiling mistress to many, but she has been a cruel jilt to me. … I have no wish to be remembered as a painter.” 110 years after his death, his painting sold for $3.25M, the highest price paid for an American painting to that point, and it indeed was exhibited in many cities afterward.

I have been told several times since my return, that I was born one hundred years too soon for the arts in our country. I have replied that, if that be the case, I will try and make it but fifty. I am more and more persuaded that I have quite as much to do with the pen for the arts as the pencil, and if I can in my day so enlighten the public as to make the way easier for those that come after me, I don’t know that I shall not have served the cause of fine arts as effectively as by painting pictures which might be appreciated one hundred years after I am gone.

Samuel Morse, 1833

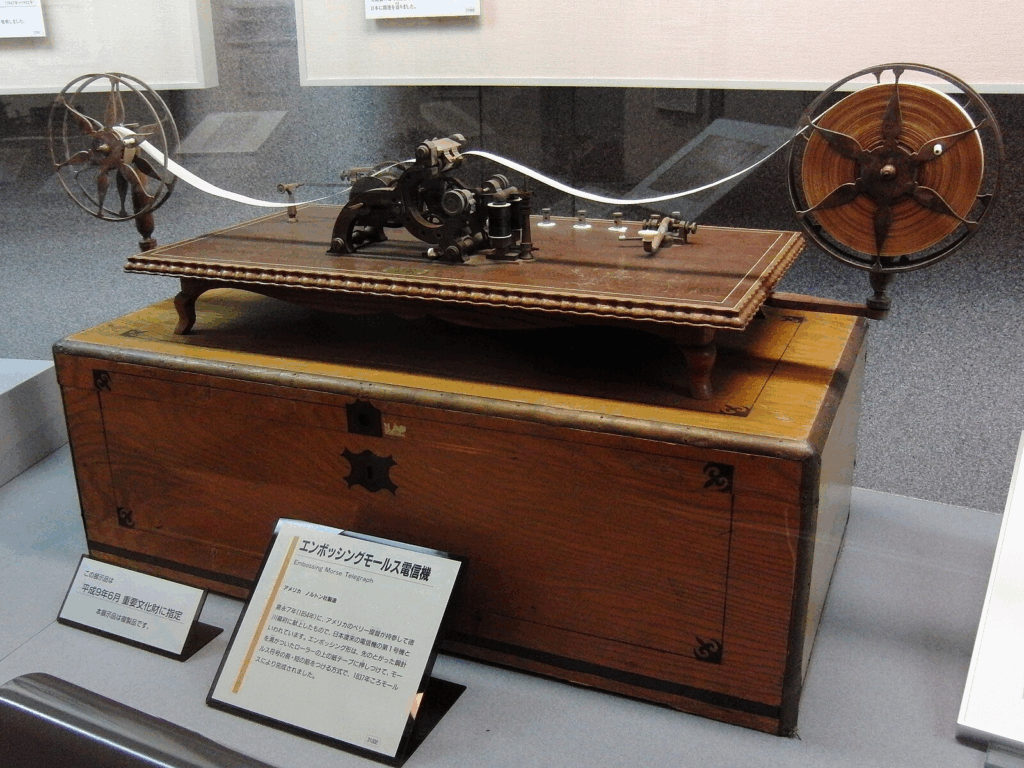

But in his yearslong attempt to transmit the ideas of European classical culture to Americans, and in his conversations with Lafayette, Humboldt and Cooper about the sharing of transatlantic intelligence, he lit a fuse of discovery and invention within himself. He boarded a New York-bound ship in October of 1832 carrying letters sent by James Fenimore Cooper, and he had heady conversations with fellow passengers about electromagnetism. Recent experiments demonstrated that electric current could travel through any length of magnetized wire instantaneously. Somewhere in that discussion, a dormant idea crystallized.

“If the presence of electricity can be made visible in any part of the circuit,” Morse said, “I see no reason why intelligence may not be transmitted instantaneously by electricity.”

.

Morse had not only conceived of the telegraph, but he had grasped at the underlying value of it: intelligence, such as the letters from Cooper that he was physically carrying, could be transmitted at the speed of an electromagnetic signal. The next decade would be consumed with translating this insight into a functioning instrument and persuading a skeptical public. But for Morse, the decisive leap had already happened out in the mid-Atlantic: the same mind that had assembled the Gallery of the Louvre as a web of timeless artistic dialogues now envisioned a noosphere, stretched across space, to carry human thought like lightning between distant points.

And while telegraph wires would eventually crisscross the entire world, they were first built in America, where, for better or worse, citizens would have an instantaneous connection to every corner of the republic.

Nerved by its power, our spreading land

A mighty giant proudly lies;

Touch but one nerve with skillful hand

Through all the thrill unbroken flies.

The dweller on the Atlantic shore

The word may breathe, and swift as light,

Where far Pacific waters roar,

That word speeds on with magic flight.

- The Magnetic Telegraph, by E.L. Schermerhorn

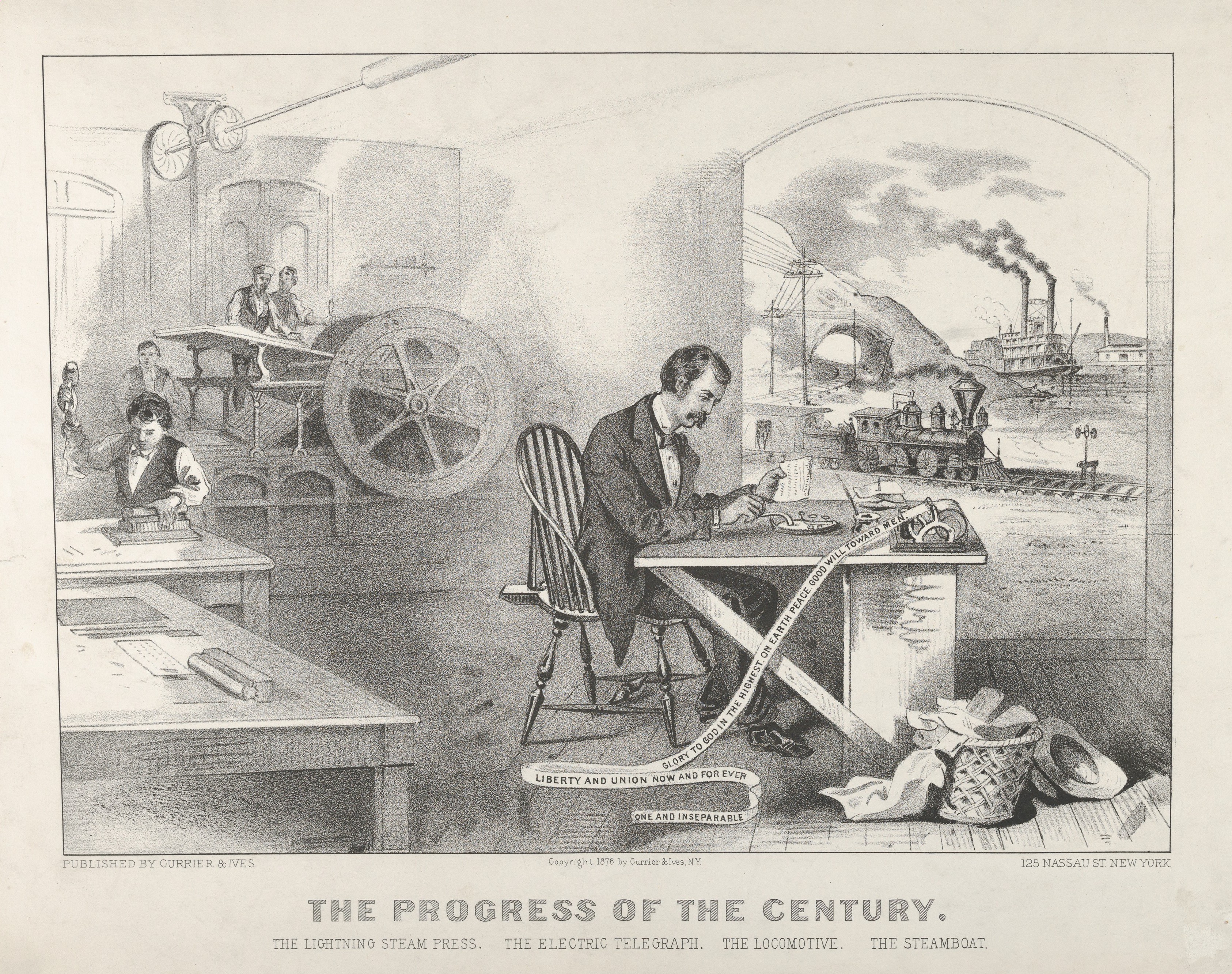

Morse became known as the “Lightning Man,” and the telegraph soon joined a rare pantheon alongside another genius of the Hudson Valley’s invention, the steamship of Robert Fulton, as American creations that bent the very notion of time and space. In 1775, it took news of bloodshed at Lexington and Concord three weeks to get from Massachusetts to South Carolina. It took up to a week to travel between Albany and New York City via sailboat. Now, it took seconds for news to travel, and mere hours for people and goods to travel:

Steam and electricity, with the natural impulses of a free people, have made, and are making, this country the greatest, the most original, the most wonderful the sun ever shone upon.

New York Herald, 1847

A transatlantic telegraph wire would eventually connect Europe to the United States, enabling von Humboldt’s desire to communicate with allies across the sea “without Napoleonic interference.” Intelligence was to be “disseminated as widely as possible without artificial restrictions.”

Locust Grove

Morse’s artistic associates, ranging from Cooper, Irving, Cole and Durand, had all in their own ways established the Hudson River as being of monumental importance to America; in The Heidenmauer (1832), Cooper asserted that the Hudson River was the equal of the Rhine in Germany:

The Rhine was an old acquaintance. A few years earlier I had stood upon the sands, at Katwyck, and watched its periodical flow into the North Sea, by means of sluices made in the short reign of the good King Louis, and the same summer I had bestrode it, a brawling brook, on the icy side of St. Gothard. We had come now to look at its beauties in its most beautiful part, and to compare them, so far as native partiality might permit, with the well-established claims of our own Hudson.

The Heidenmauer (1832), James Fennimore Cooper

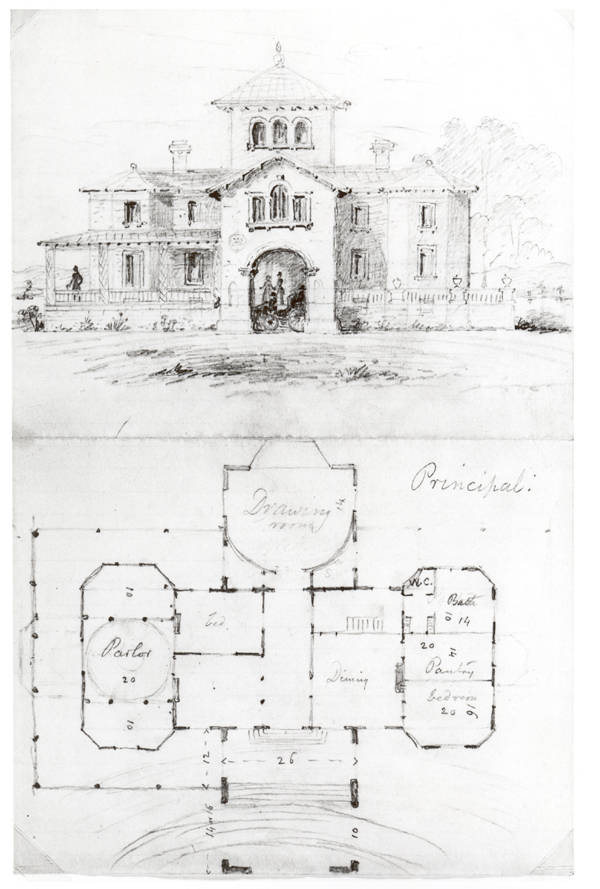

Cooper’s Rhine analogy was followed by Hudson Valley landscape gardeners like Andrew Jackson Downing and his circle, including future Locust Grove architect Alexander Jackson Davis, who promoted picturesque design on the banks of the Hudson. Downing argued that Hudson River houses should suit their dramatic landscapes, and he explicitly recommended “Rhenish” villas with towers, irregular silhouettes, and romantic siting for certain riverfront sites.

When Morse, flush with telegraph money, bought the Locust Grove estate in Poughkeepsie in 1847, the original 1830 house was plain in comparison to the new Hudson River castles. He read Downing’s books, and hired his partner Davis, who had built other villas and mansions along the river. Davis wrapped the exterior of Morse’s study in a veranda veiled with latticework, while inside, Morse filled the room with bookcases, paintings, and mementos. He also entrusted Davis with shaping the grounds. Locust trees lined a gracefully curving drive to the post road, and from his veranda, Morse could stroll along paths lined with tulips, hyacinths, and fuchsias. Trees were removed to provide an unimpeded view of the Hudson from the mansion.

Morse, in an 1826 lecture given for the National Academy of Design, commented on the emerging practice of landscape gardening:

Landscape gardening, an art in its perfection in England, and which is recently both studied and practised in our country, is the Art of arranging the objects of Nature in such a manner as to form a consistent landscape… He must to a certain extent possess the mind of the Landscape Painter, but he paints with the objects themselves. His is the art of hiding defects by interposing beauties; of correcting the errors of Nature by changing her appearance; of contriving at every point some consistent beauty so that the imagination in every part of the theatre of his performance may revel in a continual dream of delight. His main object is to select from Nature all that is agreeable, and to reject or change every thing that is disagreeable. Landscape Gardening is therefore a Fine Art; and here there is the same distinction between the mechanical and intellectual operation which exists in Architecture; it is not the laborer who levels a hill, or fills a hollow, or plants a grove that is the landscape gardener, it is he alone who with the “prophetic eye of taste,” sees prospectively the full grown forest in the young plantation, and selects with a poet’s feeling passages which he knows will affect agreeably the imagination.

Downing and Davis were of a school of thought that landscape design and architecture could imbue republican values that would inspire Americans, parallel to Morse’s belief in creative institutions doing the same. 18 years later, Downing wrote:

The love of country is inseparably connected with the love of home. Whatever, therefore, leads man to assemble the comforts and elegancies of life around his habitation, tends to increase local attachments, and render domestic life more delightful ; thus not only augmenting his own enjoyment, but strengthening his patriotism and making him a better citizen. And there is no employment or recreation which affords the mind greater or more permanent satisfaction, than that of cultivating the earth and adorning our own property.

Andrew Jackson Downing

Venetian Plots, Abolition and Religion

Starting in the 1830s, Samuel Morse began shifting his political and artistic energy into what he saw as a defense of the Republic against foreign subversion. It was a cause that his father, the Massachusetts preacher Jedediah Morse, had also taken up: the elder Morse spoke often about concerns of imported Jacobinism and the Bavarian Illuminati, which had turned the French Revolution awry.

In 1834, Morse published Foreign Conspiracy against the Liberties of the United States. He alleged that oligarchical European powers, led by Austrian Chancellor Prince Klemens von Metternich, were using the Catholic Church, including the Pope, to infiltrate and destabilize the United States via the Vienna-based Leopold Foundation, which funded Jesuit missions in America. In Morse’s telling, Jesuit missionaries were covert agents laying political landmines that could be triggered to incite unrest or fracture the Union.

These ideas were not fringe at the time. George Washington’s correspondence acknowledged his wariness of Illuminati and Jacobinite plots, smuggled in through Jesuit missionaries to cause dissension in the young republic. Austria did use papal influence to suppress Italian republican movements. The Leopold Foundation did finance Catholic institutions in the U.S. But Morse moved from healthy caution about foreign influence into histrionic nativism, even running unsuccessfully for mayor of New York City with the Native American Democratic Association.

Morse argued that America had fought itself free of monarchs, but that new immigrants “retained the mentality of subjects,” importing anti-republican habits from Europe. He wrote derisively about some immigrant groups in language reflecting the prejudices of his era.

Around the same time, radical abolitionism was gaining momentum in America. While many of the Founding Fathers had opposed slavery in principle, and identified it as a tool of the British empire, the 1830s saw the rise of a more confrontational movement that would help ignite the Civil War. By the 1850s, Morse was convinced that Britain, whose navy policed the Atlantic slave trade, was using the moral cause of abolition to weaken the United States. He noted Britain’s hypocrisy in both championing abolition and importing about 85% of its cotton from slave plantations. Sadly, Morse embraced slavery and nativism as bulwarks against what he saw as foreign meddling.

His son, Edward Lind Morse, wrote in 1914 that his father “believed that slavery was a divine institution,” and that both the abolitionists and secessionists were wrong. He was sincerely opposed to civil war, but as his son wrote, “mistaken… in his major premise.”

Morse missed the forest for the trees. His dear friends and mentors had all shared a healthy suspicion of foreign, anti-republican manipulation. But Lafayette, a staunch abolitionist, died in 1834; Cooper, who consistently portrayed slavery in a negative light, died in 1851; and Humboldt, who from Europe supported the abolitionist presidential run of John Fremont in 1856, died in 1858.

But unlike Morse, they recognized that opposing such interference was compatible with advancing liberty for all men. Cooper’s work encouraged Americans to “read between the lines” of political theater and see how noble-sounding rhetoric could mask entrenched interests. Morse absorbed this habit of mind as a young man, but in the fevered politics of the 1850s and 1860s, and perhaps after throwing himself into his work on the telegraph, his suspicion hardened into a worldview where he believed keeping the republic together required a defense of slavery, a tragic misjudgment.

Morse’s Abolitionist Minister and the Moral Divide

By the time Samuel Morse purchased Locust Grove in 1847, he had already shifted from republican artist to a nationally known inventor and lightning rod in the political culture wars. He was also, by then, openly opposed to the abolitionist movement, believing it a destabilizing force controlled by the British. As a deeply religious man, he joined the First Presbyterian Church in Poughkeepsie.

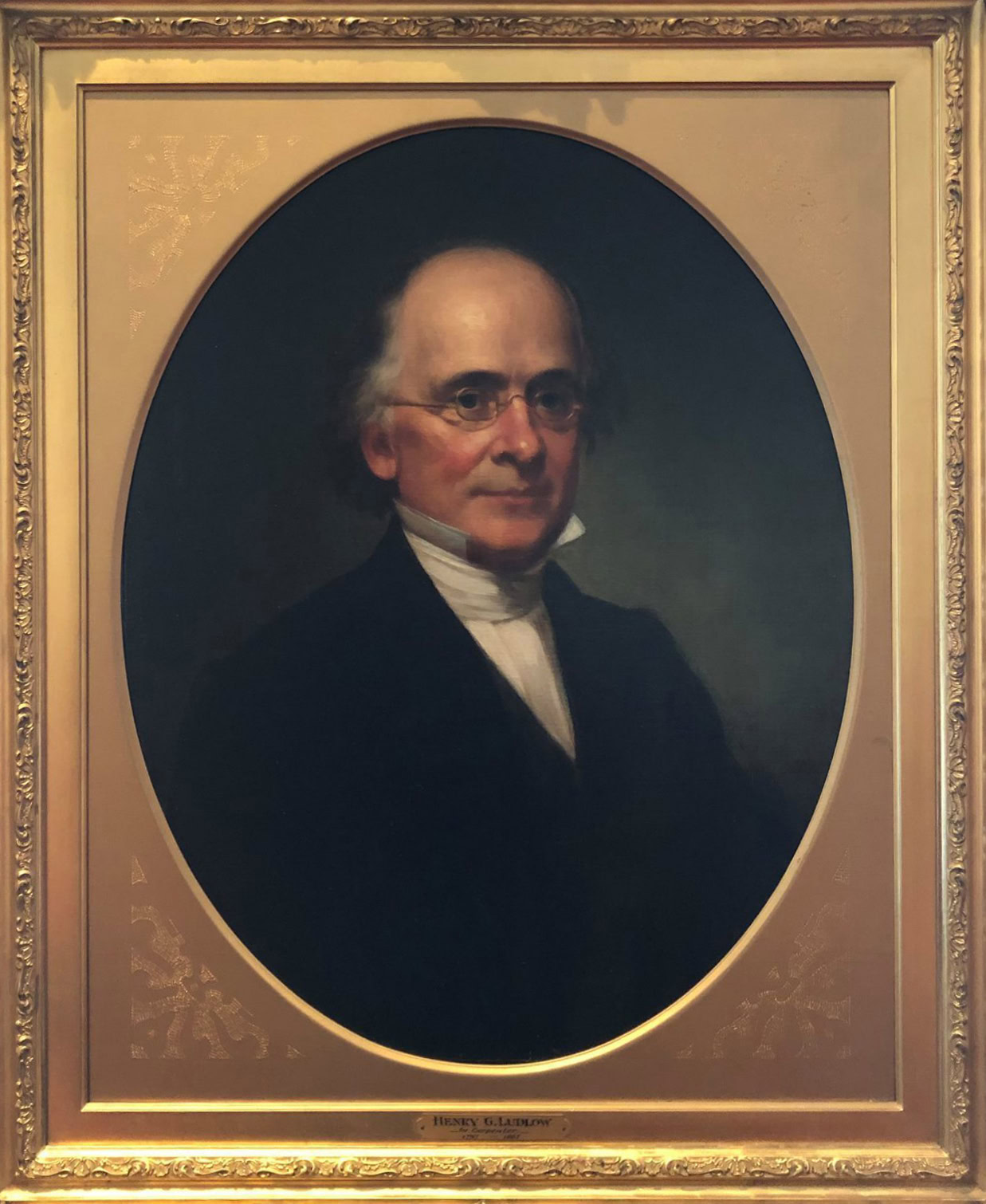

The church was led by a man who embodied everything Morse distrusted about radical reform: Reverend Henry G. Ludlow. Ludlow had already endured mob violence in New York City in the 1830s for integrating his congregation, inviting the abolitionist Grimké sisters to speak, and allegedly presiding over interracial marriages. He also played a key role in the Amistad legal case between 1839 and 1841, providing humanitarian aid to the imprisoned Africans and writing a famous letter to President (and Kinderhook native) Martin Van Buren that involved the Spirit of 1776:

I cannot keep believing that all your sympathies are, irrespective of treaties, on the side of these men, who to secure their inalienable rights, breathed the very spirit and performed the very deeds of the Heroes of ’76. May I not say that had God one hour before the deed blanched their skin, and straightened these woolly locks the united world would have applauded them, and our own Countrymen hailed their arrival here as the very men they delighted to honor. But I would ask your Excellency if these aspirations after liberty are more honorable when breathed from the image of God sculptured in ivory than from his image carved in ebony.

H.G. Ludlow to Martin Van Buren, 1839

Ludlow moved to Poughkeepsie in 1842 to lead the First Presbyterian Church, and he and Morse wrote numerous polemical letters to each other debating the institution of slavery. Ludlow “called upon him to repent him of his sins and join the cause of righteousness,” and “what a work of repentance, deep bitter repentance, have you made for yourself.” Morse fired back, “if the Bible be the umpire… then it is the Abolitionist that is denounced as worthy of excommunication. I have no justification to offer for Southern secession… it is indeed, an expression of a sense of wrong, but, in turn, is itself a wrong.”

However, Morse stayed with his church, and even donated a significant amount of telegraph stock to it in 1849, which funded a new church rectory that still stands today on Cannon Street. A portrait of Ludlow can be found at the Freedom Plains United Presbyterian Church in Poughkeepsie.

The Civil War and the Transmission of Intelligence

James Fenimore Cooper’s spy novels gave Morse and many Americans an archetype: of citizen-patriots who risked their lives in service of the nation’s survival against aristocratic duplicity, foreign subterfuge, and “political theater” that concealed imperial agendas.

In the Revolutionary War, George Washington himself was America’s first intelligence chief. He devoted more than ten percent of his military budget to espionage, creating networks in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, personally recruiting and training agents, and even cautioning his generals on how to handle the dangerous ambiguity of double spies. His Culper Ring, operating in New York, pioneered the tools of professional tradecraft, like aliases, coded writing, dead drops that allowed a weaker Continental Army to mislead and outmaneuver the world’s strongest military. As Britain’s own intelligence chief conceded after the war, Washington had not out-fought the British so much as he had “out-spied” them.

This archetype was continued during the Civil War by George H. Sharpe of Kingston, New York. A lawyer turned colonel, Sharpe personally recruited 900 members for the 120th New York Volunteer Infantry, and quickly became head of the Union’s Bureau of Military Information, the first professional spy service in U.S. military history. The BMI was the institutional continuation of Washington’s legacy: it transformed scattered information into intelligence, professionally gathered, analyzed, and deployed in defense of the republic.

The telegraph was the technology that supercharged the work of intelligence. Morse, who had spent the previous three decades laying the groundwork for telegraph infrastructure to be built, watched as his invention enabled the Union to win the Civil War and upturn the institution of slavery:

Morse did not comment on the fact, but within the whistling of bullets on American battlefields could be heard the click of his invention. Both armies extensively telegraphed military information. The Confederacy used private telegraph companies, the Union organized a Military Telegraph Department that transmitted some six and a half million dispatches. Over the course of the war a shortage of wire and other supplies silenced many of the South’s lines. Meanwhile the North strung 15,000 additional miles of wire and laid a twenty-mile submarine line across Chesapeake Bay, using a section of Cyrus Field’s abandoned 1858 Atlantic cable.

Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel F.B. Morse (2004), Kenneth Silverman

Sharpe’s BMI thrived in this environment. He distinguished between raw reports, rumors, prisoner statements, intercepted letters, and produced finished intelligence, which only emerged after comparison, corroboration, and analysis. With the telegraph, his intelligence briefs could move faster than cavalry:

Lincoln’s instinct to push the edge of the technological envelope was correct. Although his generals did not realize it at first, new technology would transform not only how they fought battles, but also how they collected intelligence and protected secrets for those battles. The Union Army’s one-year-old Signal Corps, an object of curiosity for many, eventually had 300 officers and 2,500 soldiers… The telegraph, which since 1844 had linked cities and towns with rapid communication, would have the same profound effect on both armies connecting war departments, generals, and far-flung battlefields. Union forces alone would soon be transmitting 4,500 telegrams a day over the North’s commercial network and some 15,000 miles of line its soldiers strung out.

Lincoln’s Spies: Their Secret War to Save a Nation (2019), Douglas Waller

Lincoln himself was known to stalk the War Department telegraph office in Washington, reading raw reports and communicating directly with loyal people on the ground. He drafted the Emancipation Proclamation in that very telegraph office. He was rightfully wary of plots, domestic and foreign, to undermine him and the Union, including by his Commanding General, George McClellan:

The telegraph gave [Lincoln] the capability to quickly bypass those who had been attempting to manipulate him… It is hard to imagine that someone as astute as Abraham Lincoln wasn’t at least already contemplating the new electronic medium’s ability to pierce the military’s control of information. Surely he recognized how McClellan used the telegraph to achieve a level of tactical control in Western Virginia that had been unseen in the history of war. Likewise, Lincoln observed how, as the general-in-chief, McClellan was using the telegraph to expand the scope of strategic command and control.

Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails (2008), Tom Wheeler

Lincoln removed McClellan from command, replacing him with Ulysses S. Grant. At Gettsburgh, Sharpe’s team mapped and transmitted virtually all of the General Lee’s positions, while General Ulysses S. Grant telegraphed daily orders over thousands of miles. The head of the Military Telegraph Department said of the telegraph, “orders are given—armies are moved—battles are planned and fought, and victories won with the assistance of this simple, yet powerful aide-de-camp.”

When the war ended, Sharpe received a hero’s welcome at Academy Green in Kingston with the scarred remnants of the 120th Infantry. But almost immediately, he was called back into covert service.

President Lincoln had been murdered, not on a battlefield, but as the result of a potential international plot, with the co-conspirators fleeing to London and Rome. Secretary of State William Seward, himself recovering from the knife wounds inflicted in the same conspiracy that killed Lincoln, sent Sharpe to Europe in 1867 to investigate.

Sharpe’s travels through Liverpool, London, Paris, Brussels, and Rome read like the sequel to Cooper’s novels. He traced John Surratt, one of Booth’s accomplices, from Montreal to Liverpool to the Vatican, where he had enlisted under an alias in the Papal Zouaves. He traced how Confederate agents had used British shipyards, Canadian sanctuaries, and European banks to extend the rebellion across the Atlantic. Judah Benjamin, the Confederacy’s “brains,” settled comfortably into London’s legal world, tied to the same financiers who had armed the South. While Sharpe didn’t have evidence to extradite Sharpe or Benjamin, his trip provides some confirmation that Morse’s suspicions of British and Venetian subterfuge had merit.

However, the subterfuge was aimed at Lincoln and the Union, on the behalf of the institution of slavery. When General McClellan, after being removed from command by Lincoln, stepped up to run for president as a pro-slavery Democrat in 1864, Morse threw his influence behind McClellan’s presidential campaign, emerging as one of the most prominent “Copperhead” voices in New York. He denounced Lincoln as a tyrant and cast abolitionists as the true conspirators against the Republic.

Wealthy allies like August Belmont, Samuel Tilden and Horatio Seymour joined him, and together they tried to marshal Democratic strength to unseat Lincoln in the 1864 election. William Cullen Bryant’s Evening Post reported on one of their meetings in New York City:

The rich men of New York are to supply the money… for an active and unscrupulous campaign against the government of the nation, and in the behalf of a body of rebels now in arms… to hand the government over, if they can, to the malignant slave-holding oligarchs who for nearly two years have been slaughtering our sons.

Evening Post, February 1863

Lincoln lost New York City by 37,000 votes, but overwhelmingly won elsewhere, in a powerful referendum on the direction of the nation.

It marked the bitter end of Morse’s political life: the same man who once transmitted Lafayette’s republican ideals and gave the Union its telegraphic nerve system had worked tirelessly against the very president who wielded that invention to save the nation.

To Republican Institutions!

Samuel Morse’s life traced the arc of American genius in the 19th century: brilliant, contradictory, visionary, and at times tragically misguided. He was a cultural leader who wanted to elevate the American eye, a republican warrior who intrigued with Lafayette and Cooper, and an inventor whose telegraph transformed the very nature of intelligence, war, and communication. Yet he was also a man who lost his way in the political storms of his age, mistaking the defense of slavery for the defense of the Republic.

After his death in 1872, the city of Poughkeepsie honored him in the Presbyterian church where he had worshipped for decades. Mayor Harvey Eastman proclaimed that “wherever the electric telegraph is known—and that is wherever there is civilization—the intelligence of the death of Prof. Samuel F. B. Morse, the man who taught lightning to speak the language of men, has been received with profound regret. The glory of his achievements and eminent services to the world are recognized in every part of the globe.”

Reverend Francis B. Wheeler (the successor to the deceased abolitionist Reverend H.G. Ludlow) said “our noble river is immortalized by the name of Fulton, while its banks and our city have been rendered illustrious by the name of Morse.” Reverend John Raymond, president of Vassar College, said Morse “manifested a cordial sympathy with every institution and instrumentality which promised to aid in the enlightenment of mankind.”

That legacy is enshrined in the U.S. Capitol itself. In Constantino Brumidi’s great ceiling mural, Science, the goddess Minerva instructs a circle of American innovators: Benjamin Franklin with his kite and key, Robert Fulton with his steamboat, and Samuel Morse with his telegraph. The painting is a physical reminder that the progress of our nation depends not only on politics and law, but on genius and discoveries directed toward the advancement of mankind.

An 1877 effort to build a statue for Morse in Poughkeepsie met with reminders of his Civil War missteps, which will never be forgotten. But despite it all, Morse’s true legacy was in the service of what his dear friend, the Marquis de Lafayette called for in 1832. Morse presided over a 1832 Independence Day dinner in Paris that drew many Americans and French allies. He toasted the 75-year old Marquis de Lafayette, who would pass away within two years, celebrating “the great principles of rational liberty, of civil and religious liberty,” and praised him as “the hero whom two worlds claim as their own.”

Without knowing the long path Morse’s life would take, with the triumph of the telegraph, the institutions he helped found, or even the political storms he would stumble through, Lafayette saw in him what mattered most: an American genius animated by art, faith, and a devotion to the Republic’s future. The old general lifted his glass to salute not just Morse, but the promise of a young nation still perfecting itself. He called Morse the “worthy representative of the artists of the country,” and concluded with:

“To Republican Institutions, the prolific Daughters of American Independence!”