As a local marketing agency that celebrates the potential of the Hudson Valley and Catskills community, we present this historical, philosophical and political look into the murky depths of the New York City reservoir system. We are proud to co-publish this in partnership with New York Energy Alliance, a statewide grassroots group that advocates for reliable and affordable energy for New York families and businesses.

A Tale of Two Regions

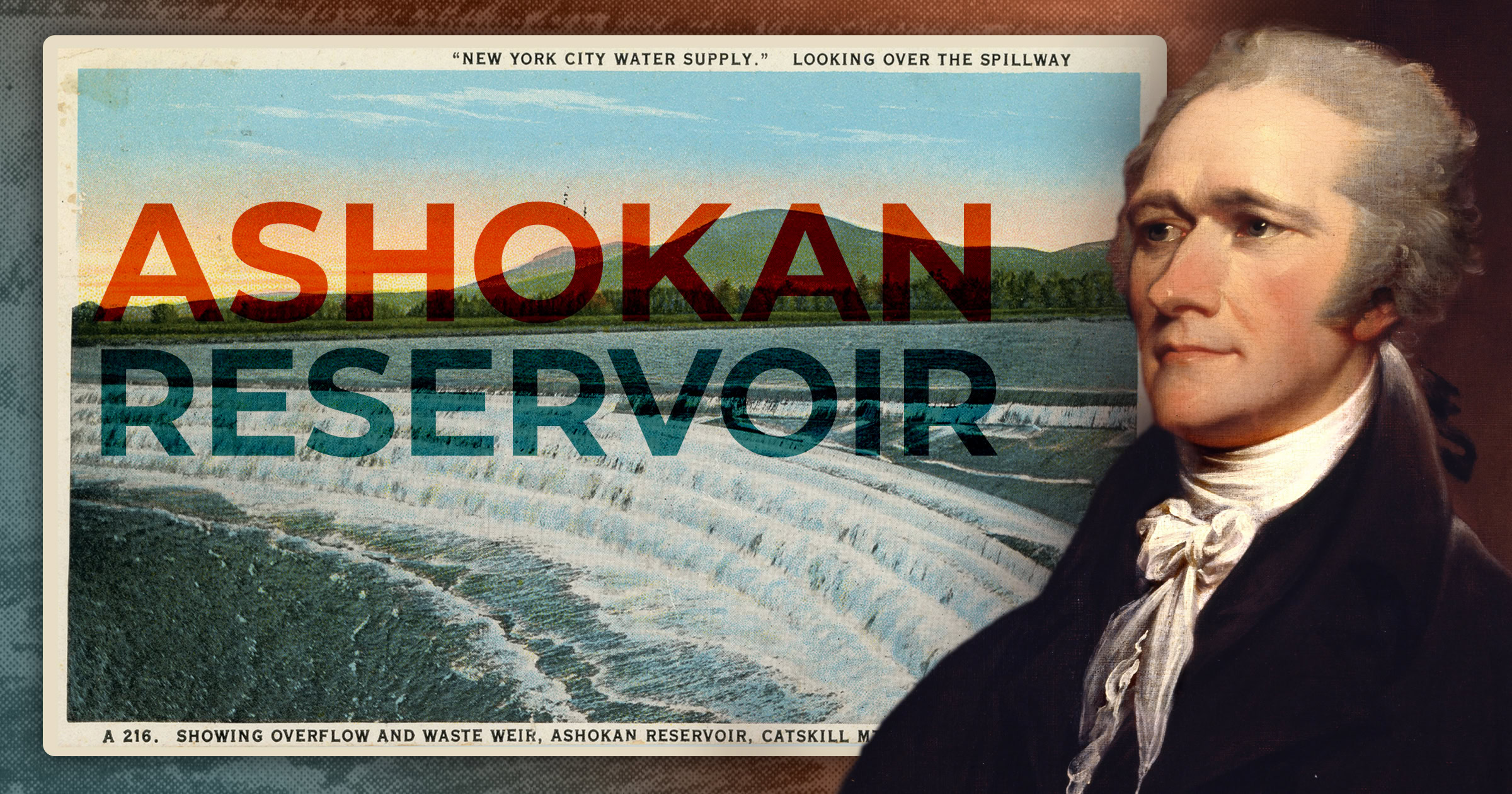

Many people in the Hudson Valley and Catskills remember the development of the New York City water system at the Ashokan Reservoir and others as a violent taking: visions of drowned villages and peeking church steeples, relocated graves, drenched farmlands and angry villagers abound. Today, the reservoir stands as one of many placid local areas for recreation and contemplation, as tax dollars flow in from New York City in exchange for keeping the land underdeveloped.

But the real story of the Catskills and New York City’s water system is so much more than just the act of building it: Ulster and Delaware Counties have been home to a century-long battle between equitable growth and stagnant entropy, between false dichotomies and truth, and a debate about the ideals of our nation that dates back to its founding.

This battle becomes more relevant as we consider the conditions in the New York City watershed region: the evolution of the water system and subsequent restrictions on development are directly linked to a lack of local control over our destiny. As a critical deadline approaches for New York City to maintain its stranglehold over the region, let’s dive into some history.

Hamilton vs. Burr: The First Battle Over Water

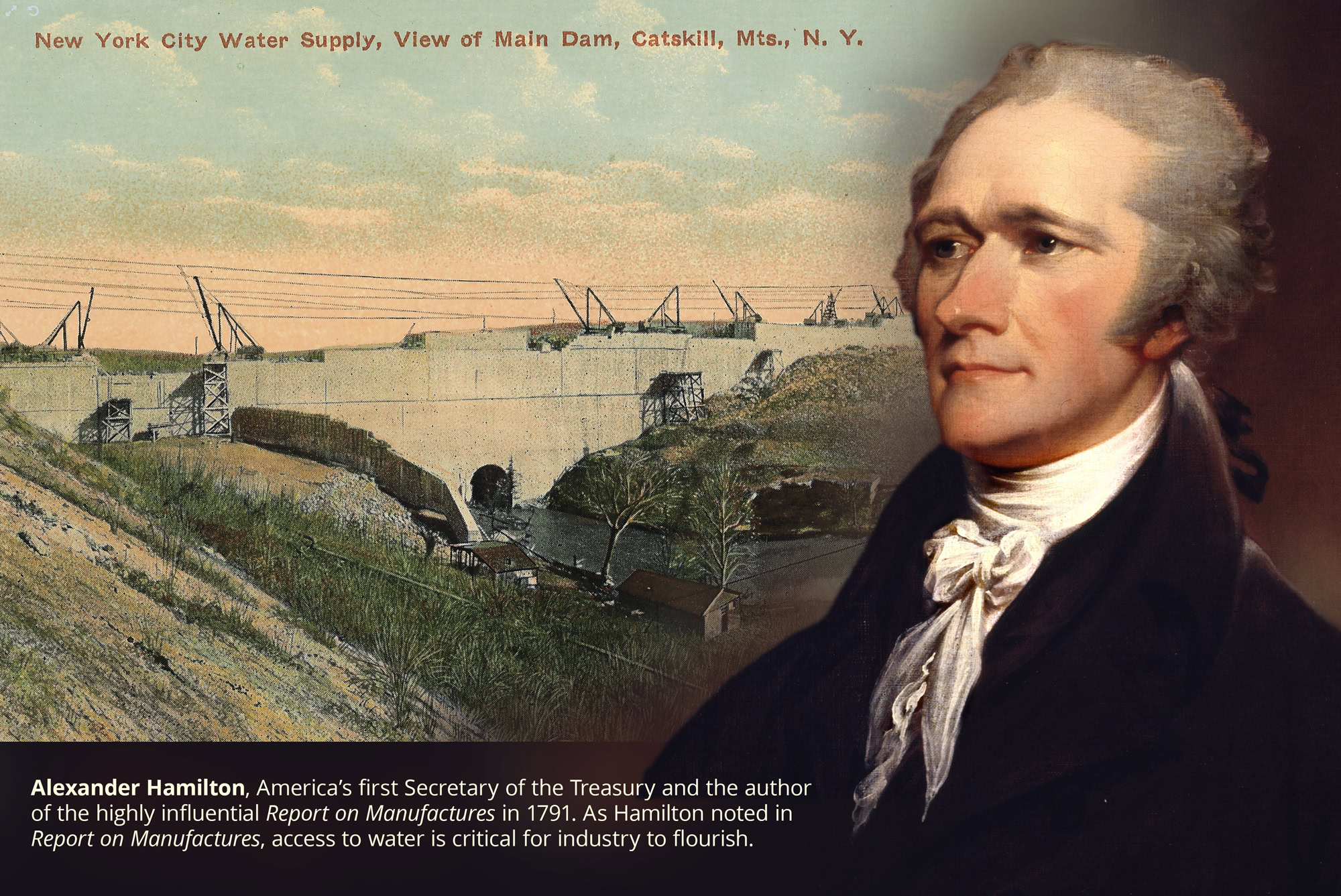

In the 1790s, New York City had about a 99% lower population than it does now: 33,000 vs. 8.2M. But it was the largest city in the nation, and rapidly growing thanks in large part to the economic policies of Alexander Hamilton, America’s first Secretary of the Treasury and the author of the highly influential Report on Manufactures in 1791.

The basis of Hamilton’s economic policies were to use a national bank to create a stable economic environment that could leverage credit to make long-term infrastructure investments in roads, canals and ports, which could then enable industrial development and an increase in the productive power of labor across agriculture, mining, manufacturing and other useful industries. This increase in production would be protected by sensible tariffs, which ensured that Americans would be exporting valuable goods instead of raw materials, and it led to port cities like New York becoming rapidly expanding economic hubs.

As Hamilton noted in Report on Manufactures, access to water is critical for industry to flourish. And in 1798, New York City was facing a water crisis: not just for industry, but for its basic survival. A series of yellow fever epidemics were caused by contaminated drinking water, and the Common Council of New York was seeking solutions. In the same year that Thomas Malthus wrote his loathsome Essay on the Principle of Population, New York City was seeking infrastructure solutions to bring clean water from where it was, to where it wasn’t, in order to support a growing and healthy population.

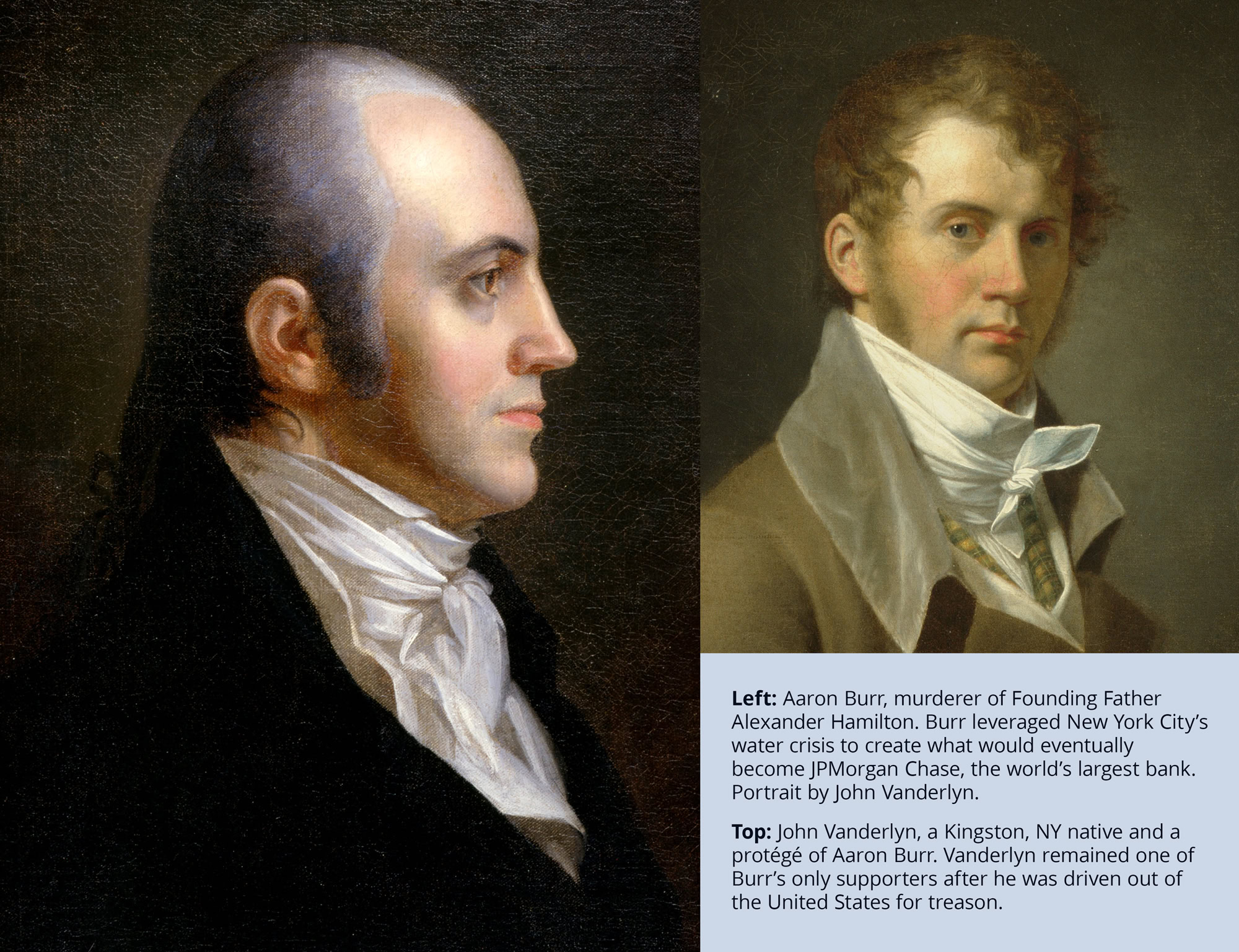

In this environment, Aaron Burr, a political rival to Hamilton and his eventual murderer, saw an opportunity: he proposed the creation of a private water company called The Manhattan Company. Nominally, the Company was being created to bring clean water from the Bronx River to the city; and he maneuvered to gain support from Hamilton himself. But hidden in the charter of the Manhattan Company was a clause that allowed for Burr to use surplus capital for “monied transactions,” a veiled reference to the creation of a private bank.

Burr leveraged New York City’s water crisis to create a competitor bank to Hamilton and the Federalists’ Bank of New York; this bank would offer favorable terms to Burr and his elite political allies. Instead of upholding the Hamiltonian idea of enabling growth and industry, the Manhattan Company built minimal water infrastructure and it was an active liability, not an asset, to the city. The water supply was insufficient for the growing city and was riddled with filth, and was directly tied to multiple yellow fever outbreaks as well as fires raging out of control. The City’s population wasn’t being held back by natural resource limits to growth, as Malthus had predicted, but by usurious and traitorous financial schemes.

Burr’s perfidy toward Hamilton was one of their many disagreements that led to their tragic final confrontation in 1804. Burr’s crimes caught up with him when he was tried for treason in 1807, was narrowly acquitted, and died bankrupt in a Staten Island boarding house in 1836.

Beatrice Reubens, writing in Political Science Quarterly in 1957, said that the company’s existence “blocked municipal enterprise until the tide of public sentiment turned… the inadequate water supply endured by New York City for so long was one of the most serious consequences of the failure of successive generations of Manhattan directors to either expand their water service to meet the growth of the city or to dispose of their water rights and property.”

The underdevelopment of local water resources, such as from the Bronx River, led the City’s eventual aggressive pursuit of upstate sources, starting with the Croton Aqueduct in 1840. After losing its monopoly on providing the city’s water, the Manhattan Company still had to maintain its standing as a water provider; they ceremoniously pumped water from a well once a day until 1923, when they dropped the charade. The Manhattan Company merged with Chase to become Chase Manhattan Bank in 1955, which then merged with J.P. Morgan & Co. to become J.P. Morgan Chase in 2000. The Burr-Hamilton dueling pistols are kept in J.P. Morgan Chase headquarters in New York City.

The Rise of NYC’s Mega-Infrastructure Projects

The builders of the Croton Aqueduct believed that they had covered the needs of the city for decades to come; by 1848, the growth of the city already had outstripped the capacity of the infrastructure. A large reservoir in Central Park, tapping into the Bronx and Byram Rivers, a second Croton Aqueduct, and a new Croton dam, the largest in the world, were completed by 1906. But it still wasn’t enough, and this is where vulnerable Ulster County and the surrounding Catskills region were targeted.

Ever since Johannes Hardenbergh had acquired what is known as the “Hardenbergh Patent” of two million acres across Ulster, Greene, Delaware, Orange and Sullivan Counties from the British Crown in 1708, the region had failed to develop at the pace of other areas in the state. By unleashing fire and devastation upon Kingston in 1777, the British Empire ensured the deliberate underdevelopment of the region, solidifying Albany as the new upstate epicenter.

In the 1800s, the region chased boom and bust cycles of the tanning industry, bluestone extraction, logging, and charcoal production, all of which were tapped out or financially unviable within decades. Due to the uneven terrain, large-scale, capital-intensive farming was hard to pursue, leading to subsistence-level farming practices.

Instead of relying on a productive economy for taxes, the county had to rely heavily on property taxes, which frequently led to defaults. A series of poor decisions and bad judgment by figures like Hardenbergh’s descendant, Shawangunk Supervisor and Ulster County Board of Supervisors leader Cornelius A.C. Hardenbergh, led to populist posturing about not paying taxes to the state on foreclosed land; resulting in Ulster County being the only tax delinquent county in the state in 1884.

The crisis forced Hardenbergh and his peers to set an ignominious new precedent for Ulster County: instead of developing infrastructure that could lead to investments in raising the productive capacity of labor, and therefore a higher standard of living for local residents, they sold off 32,731 acres of land to New York State to settle its tax debts. In turn, the land was designated as Catskill Park, a State Forest Preserve that would remain “forever wild.” While Ulster County would clear debt and receive tax payments on the property, it was in exchange for remaining in a state of arrested development, making the deal a Pyrric victory with long-term consequences. Recreation and conservation remain at tension with the region’s ongoing housing, affordability and economic crises to this day.

Even in 1885, the wheels were already in motion for the Ashokan Reservoir to be built. The text of the Catskill Park bill said that watershed protection was a principal reason for its establishment. In no coincidence the following year, Scientific American published an article describing the framework that New York City would eventually adopt in constructing its Catskill waterworks. The high peaks of the Catskills Mountains created catchment basins for water, while the elevation of the region compared to New York City meant that water could be propelled by the effects of gravity.

By 1907, construction on the Ashokan Reservoir had begun. But just as New York’s water crisis in 1798 was exploited for personal gain rather than long-term development, the Catskills’ water resources would be claimed in a way that prioritized NYC’s needs over regional prosperity.

Ulster County’s Economic Handcuffs

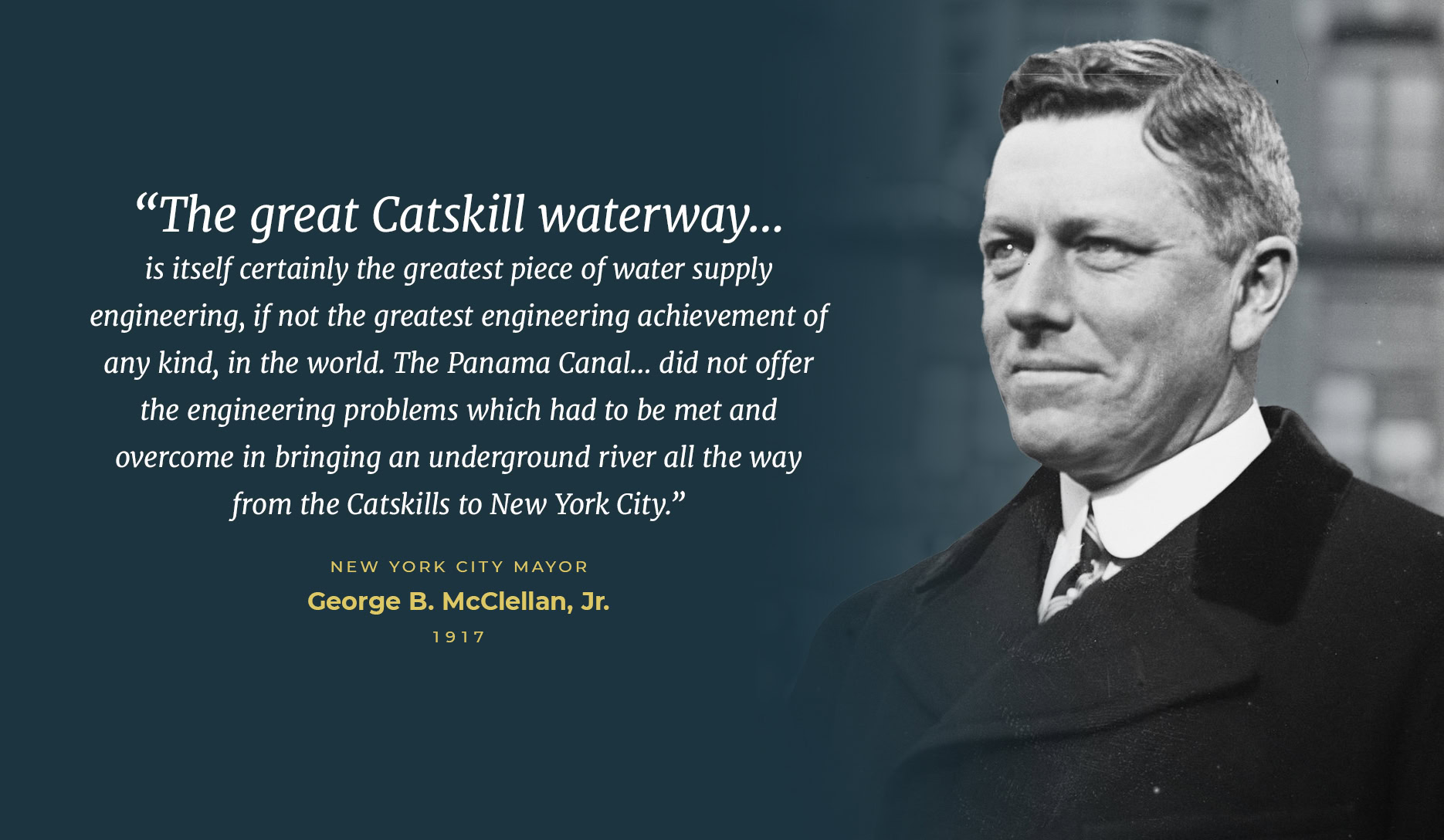

The initial taking of the Ashokan Reservoir has been well-covered elsewhere; almost to the point of obscuring the continuing effects of it. But the project, completed in 1917, was widely considered to be the greatest mega-engineering project of the world, even greater than the 1915 completion of the Panama Canal.

The aqueduct stretched 120 miles to its end on Staten Island. It was built through pressure tunnels carved deep into solid rock, which transported water beneath the Hudson River near Storm King Mountain via the Rondout Siphon, which descends 1,114 feet below sea level.

The waterway was a triumph of Hamilton over Burr. Government-backed mega-infrastructure was going to enable New York City to get some of the most abundant and high-quality water it ever had access to. New York City’s population doubled from the time construction began on the reservoir to when it was finished. By the time the city finished most of its Catskills water infrastructure projects in the 1960s, its population had grown from 3.4M in 1900 to 7.9M in 1970.

Unfortunately for the Catskills and Ulster County, the short-term thinking of Burr, and later Hardenbergh, would end up being the lasting legacy of the water system. Instead of experiencing the halo effects of one of the world’s largest infrastructure projects in its backyard, and being able to build more infrastructure and industry around the reservoirs, one critical decision over water filtration would lock the region in a state of arrested development for over a century (and counting) to come.

The Filtration Plant That Was Was Promised

“The question that would come to dominate New York City’s relationship with Catskill residents in the 1990s—should it build a costly filtration plant to improve water quality or instead enact strict regulations to reduce pollution on the watershed—first reared its head, albeit less starkly, seventy-five years earlier.”

David Soll, Empire of Water: An Environmental and Political History of the New York City Water Supply (2013)

The initial designs for the reservoir included building a $17.5 million filtration plant in Westchester to enable the maximum amount of purity and clarity of water. But in 1915, Ashokan Reservoir engineer John Freeman backtracked, saying he “could see no reason why this water cannot be prudently delivered for some years without filtration, if the present financial needs of the City require deferring such expenditures.”

This deferral ended up killing the possibility of building a water filtration plant. Instead, New York City realized that it was far cheaper to prevent Ulster County and the Catskills villages from developing anything around the reservoirs, relying on undeveloped nature to filter the water.

The Filtration Avoidance Determination (FAD): Keeping the Catskills Poor for NYC’s Water?

This decision to avoid a water filtration plant, which would have cost over $5B in 1915 when adjusted for inflation, meant that the usual benefits of hosting mega-infrastructure projects never got passed on to Ulster County and the Catskills.

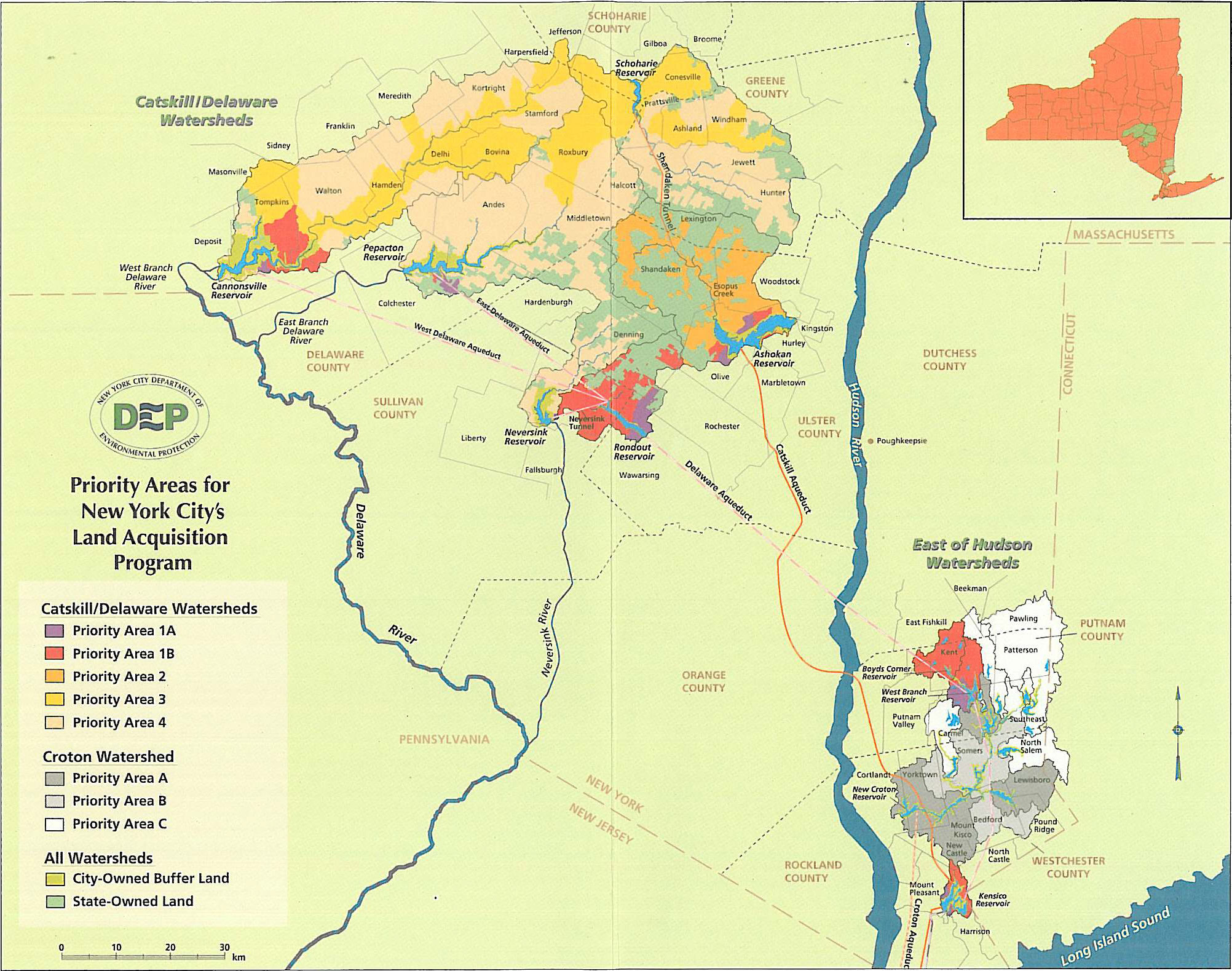

The building of the reservoirs usually meant that there would be a decade of work for local job-seekers. But the long-term negative effects have far outweighed that: the surrounding land was kept underdeveloped through regulation or bought outright from 1997 onward as part of New York City’s Land Acquisition Program to avoid having to build a filtration plant. In Ulster County alone, 32% of the total land mass is protected from development.

While no full accounting of the 1915 decision to forgo a filtration plant exists, a reasonable estimate suggests the economic burden on the Catskills region has been staggering*:

- $100M/year in lost development (industry, real estate, small business, etc.) from 1915–1980, increasing to $500M/year from 1980 onward

- $10M/year in lost tax revenue from 1915–1980, increasing to $50M/year from 1980 onward

- $25M/year in lost population growth from 1915–1980, increasing to $100M/year from 1980 onward

Applying a 3% annual inflation rate, the total impact is estimated at:

- $29B in lost development investment

- $2.9B in lost tax revenue

- $6.1B in lost population growth

- $38B total economic loss

When assessing the rates of poverty, opioid addiction and other forms of misery in the host communities, it’s clear that the decision to not build a filtration plant has had a devastating cost while saving New Yorkers a relatively small amount of money, which could have been raised through bonding and paid off over time.

“When they flooded the valley of the East Branch, they inundated good dairy farms on the river flats. So there was a permanent disruption of our economy. Of course it has put us in an enviable tax position, and it’s been a great help to the county taxes. And now we’re getting renown as a great fishing center. But you see, we lost 12-month enterprises when we lost those dairy farmers, and the fishing is highly seasonal. It hurt a lot when we lost those dairies and creameries.”

Wallace Wynkoop, Colchester Supervisor 1961

A Watershed Moment for the Catskills

In the 1990s, New York City and the reservoir host communities reached an inflection point. New federal law required that any municipality with a population over 10,000 had to filter its water or acquire a Filtration Avoidance Determination (FAD). The only way to get a FAD is to prove that there are enough natural barriers and preserved lands around the municipality’s water source.

“It should be that our best management practices are enough… now they want to control life on the hills. Well, they moved us out of the hills. They put us on the hills in the first place.”

Assemblyman Dick Coombe, R-Grahamsville, 1990

Watershed communities began formally organizing their efforts to mount a counterforce to New York City’s aggressive land acquisition efforts around the reservoirs. The city’s approach, coupled with a century of economic underdevelopment, led to a spiraling of inequality and gentrification: real estate prices were driven up without increasing local wages, which meant that if land wasn’t being bought by New York City, the only other purchasers were wealthy second homeowners.

“While these land acquisitions may be protecting the city’s water, they also may be causing a new wave of indirect damages to watershed communities—a slow-moving expulsion. (Hoffman 2005, 2008, 2010).

Poverty rates increased throughout the 1990s, and approximately 40 percent of renters cannot afford fair market rents in these communities. This has affected the children of current residents who cannot find housing of their own. Enforcement of water regulations is also keeping business out, which negatively impacts their ability to find work.

More than 60 percent of Olive’s land is already owned by the state or the city. There is precious little space for people to live, and the tax burden has shifted to fewer and fewer residents. Taxes are based on assessed property values, and because city-owned land is without structures, the city pays little in taxes.”

– Taking Our Water for the City, April Beisaw, 2022

As the deadline approached to either committing to a filtration plant or a FAD determination approached, a third party emerged in the negotiations: New York City’s powerful and well-funded environmentalists. Most prominent among them was Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the lead attorney and external face of Riverkeeper and the National Resources Defense Council, who earned the derisive moniker “Fifth-Avenue Environmentalist” from former Town of Hunter supervisor Anthony Bucca.

“Spending so much on filtration at a time when every level of government is crying poverty would no doubt undermine watershed protection. There would be little, if any, money left over for buying buffer lands, regulating development, beefing up enforcement and otherwise protecting the supply. In fact DEP officials have said that the high cost of filtration would probably spur calls for the city to sell some of the buffer lands it now owns. Filtration would also foster a sense that watershed protection was unnecessary.”

Riverkeeper, The Legend of City Water, 1991

The upstate towns wanted less stringent regulations on development and farming, and were ready to force the city to build a filtration plant. The environmentalists wanted more environmental regulations and more aggressive land-buying, and positioned themselves as the financial saviors for New York City, as their strategy was far cheaper than building a filtration plant. New York City was caught in the middle, although they were far more amenable to RFK Jr. and the environmentalists in the end.

“New York City… they feel, I guess, that in the watershed they have to restrict development, which is a very touchy situation.”

Olive Town Supervisor Berndt Leifeld, 1990

The 1997 New York City Watershed Memorandum of Agreement secured New York City’s Filtration Avoidance Determination by pledging over a billion dollars to what’s known as the Land Acquisition Program. When New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani mercifully loosened some of the protections against development, he was blasted by Robert Kennedy Jr. in the press for not sufficiently “favor[ing] New York City,” despite the city already facing 125 lawsuits for damages over the onerous enforcement of the regulations.

The Land Acquisition Program continued largely unaltered until 2024, when the Delaware County acquisitions were stopped. Ulster County acquisitions continue full steam ahead.

“This change is welcomed as we grapple with issues such as a lack of affordable workforce housing, a limited amount of capacity to extend or develop municipal sewer and water systems, an aging and decreasing population base and an increase in the local cost of living.”

Delaware County Board of Supervisors, 2024

The very scientific basis of the Land Acquisition Program was called into question in a 2005 essay by environmental philosophy Mark Sagoff, who dubbed the concept of natural filtration “The Catskills Parable.”

He wrote that impurities and pathogenic microorganisms are more likely to be introduced into the water by the surrounding natural landscape (such as from animal scat) than removed by it; and that the determination of the amount of land that needed to be acquired was arrived at through political and not as a means of environmental necessity:

“Few of us wish to admit that we benefit from nature not by preserving but by “improving” it—for example, by plowing a field, building a road, constructing a house, drilling a well, damming a river, farming a salmon or oyster, or altering a genome. Most of us would rather believe that Nature knows best. We will therefore repeat… the Catskills parable even though it is factually false.”

– Mark Sagoff

Looking Ahead: A Chance to Reclaim Regional Prosperity

There is an upcoming chance for Ulster County and Catskills reservoir communities to change the narrative: New York City’s impending 2027 deadline to renew its Filtration Avoidance Determination (FAD) is approaching.

It’s not just a bureaucratic hurdle—it could be a historic turning point in the long interplay between two irreconcilable economic paradigms: the Hamiltonian vision of national infrastructure-led growth and an short-term, exploitative philosophy that has kept the Catskills in a state of engineered underdevelopment for over a century.

The fundamental question remains: Will New York City finally bear the cost of a filtration system, allowing greater development in our communities, or will the status quo continue—preserving the purity of urban drinking water at the expense of rural economic opportunity?

There’s recent precedent: Portland, one of the few American cities that was applying for filtration avoidance, has been given ten years to build a $2.1B filtration plant due to new forms of contamination being discovered.

As meetings begin and negotiations unfold, the people of the Catskills and Hudson Valley must ask ourselves: Is it time to finally challenge the narrative that has governed our land for over a century? And more importantly—do we have the political will to fight for the future?

Be sure to sign up for the New York Energy Alliance newsletter to receive Part Two of this series, where we will publish interviews and anecdotes from former and current elected representatives, economic development planners and professionals, farmers, small business owners and residents of the Watershed.

Notes

*Data Limitations:

- No official government-led economic impact study exists on this topic. These estimates are built from reasonable economic modeling based on historical trends.

Why 1915?

- NYC had already considered filtration in 1915 but instead pursued watershed protections. This analysis assumes that without this decision, some level of controlled development would have occurred.

Development Loss Assumptions:

- Estimates reflect lost commercial, industrial, and residential growth—not just direct NYC land acquisitions.

- 1915–1980: $100M/year reflects smaller-scale restrictions before aggressive land buys.

- 1980–Present: $500M/year reflects more stringent regulations and expansion of protections.

Tax Revenue Assumptions:

- 10% of estimated lost economic activity is used as a proxy for lost tax revenues.

Population Growth Losses:

- The inability to develop industries and housing restricted job creation and long-term population growth.

- A conservative $25M–$100M/year estimate reflects the compounded economic loss of outmigration and stagnation.

Inflation Adjustment (3%):

- A standard 3% average annual inflation rate is used to convert past losses into 2024 dollars.

- Adjustments based on historical CPI trends ensure estimates reflect modern economic values.